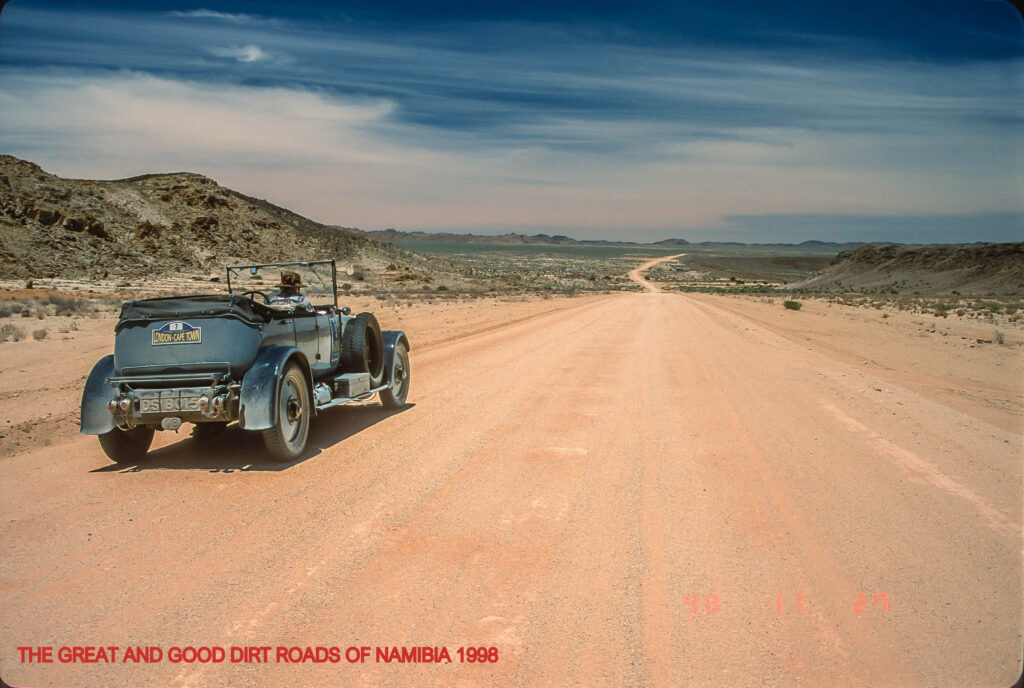

We were probably only about 150 miles from the Atlantic coast of Africa to our right and a similar distance from the Kalahari Desert to our left. The twilight was perpetually lingering as the sun setting over the Atlantic was unhindered by mountain or cloud. Presently though, the lorry driver, who must have been aware by the shadows, that we had been following him, started flashing his indicators, his stop lamps and then his green overtaking lamp as he was pulling off onto the hard of the desert for the night. As we passed a deafening horn blast accompanied by the drivers burly arm waved us farewell: we now felt very lonely as nothing else either coming or going had been seen on that road.

We had been cautioned not to drive in Africa by night principally on account of the poor roads but also large animals came out from the bush suddenly and hitting one would be very messy and dangerous: though unsaid the human menace was probably more real.

The long lingering twilight had now passed and dusk had descended at Mariental where on checking the fuel I found we only had about 3 gallons, perhaps enough for only 15 miles at the current rate of consumption and seepage. The Lanchesters best ever 11.75 MPG would mean we could easily make the next 180 mile leg comfortably on just the main tank. But those head winds were confirmed to persist by the garagiste and the road would be rougher with hill country to pass so both tanks were again replenished restarting the noxious odour and our fears of a fire.

Mariental is a 1 horse burg with a paved central crossroads, a garage, a drug store and some shanty accommodations completed by a rusty tin church. Namibia is one of the last refuges for a natural night without light pollution and on leaving we were plunged into a solid black moonless night: we presumed this to be one, “of the all kinds of daylight left” promised from Keetmanshoop!.

So important was the knowledge of a full moon for travellers that in the 18th century time pieces showing the aging of the moon were a fashionable gadget. We now would appreciate their concerns.

The headlamps, Marchal 8” twin reflector sealed lens units, from a Ferrari Superfast grafted neatly into the original Lanchester lamps were superb. Utilising both dipped and head beams simultaneously 400 Watts of light tamed the desert road for miles ahead. Occasionally we saw wildlife scurrying across in front of us but our enthusiasm was not now for a safari as it had been on previous days: now it was on how soon to get there intact.

“Oh you will find us easily”had said the manager to Susie, “as you drop down from the hills you will see green street lamps, a petrol station and about a mile up on the left you will see us with a gateway made from fossilised trees.” Well that sounded easy enough, but green street lamps? This and many other thoughts kept replaying on my mind mile by interminable mile.

In all respects the 40 horse was purring along beautifully accepting the rough lorry defiled road surface like a thoroughbred shire horse: had I known then, what I found out a week later in Cape Town, that both front axle springs were broken, I should have arrived at the hotel in a state of complete nervous breakdown. But ignorance IS bliss and as it was the next 180 miles, each of which trudged away apparently even more slowly than the last, was, in hindsight, a marvellous drive.

The headwind finally gave way at about 2300hrs and with the petrol vapours gone for the second time we bucked up enormously and clearing a crest in the hills there below was a glow from those eerie green lights promising of Keetmanshoop.

The garage was still open so I filled only the main tank and reconfirmed the hotels whereabouts: all was well. Those green street lamps make an African into a fiendish apparition with only the whites of his eyes and his powerful teeth flashing in dark space: I was apprehensive when they jumped onto the running boards to help show the way. I would have no help and drove off without collecting my change!

Turning in at the fossilised trees gateway and parking in front of the tiered steps leading to the reception I realised just how tired I was when a young uniformed black girl came out onto the steps and staring at us clapped her hands over her face and let out a giggling shriek whilst disappearing back through the double doors. “Fucking cheek” I roared, “Where’s the bloody porters. Do they think I’m going to drive this crate

360 miles nonstop and carry my own luggage? Lazy bastards!” Whereupon the entire staff headed by the manager came out onto the steps and started singing, dancing and clapping a welcome as only Africans can make! In bewilderment I wiped the dust from my lenses and felt a touch heroic for a moment: quite emotional really at that point of exhaustion.

The luggage was unpacked and swiftly taken to the room. Susie was virtually carried shoulder high and I placed the 40 horse in a lockable barbed wire cage for the night, one of a block of 6 though only our car was so protected. I fairly caressed its lovely headlamps for seeing us through such a tough night’s journey: there not being the faintest whiff of petrol about the car now.

The Swiss Serbo-Croat manager had posted the young girl to keep a watch for our arrival and was amazed at our appearance being covered from head to foot, from rad to tail pipe, in white chalk, “Why don’t you have a roof?”he asked. Why, Indeed?. He had the biggest steaks ready, the coldest beer and deep apple pie and custard. Life was really worth living, again. That long, bleak, dusty, lonely, rutted road was suddenly a vanishing memory.

A quick wash and we sat down to dine at 32 mins past midnight. I couldn’t really eat too much as fatigue was calling me to my bed. The perfect hotel manager consoled me with the promise of bacon & eggs for breakfast, toast and thick cut marmalade and Indian black tea. Weary but elated we left the dining room for bed.

The room was stark, clean and severe like a monk’s cell but with the added attraction of dead rat odour, so common and so pungent in Africa & Asia. From this I was perfectly prepared to wake up in the morning dying from Legionnaires Disease! Nothing could keep my thoughts from sleep as I, like the young Robert Louis Stevenson, sailed in my cot out from this world into the bliss of dreams that the richest man could not, yet would dearly, pay for.

That was not the only hard or the longest single journey. My fish-allergy made us drive from Pomfret, Kalahari to Cape Town South Africa via Lamberts Bay: 1150 miles mainly on dirt: but that’s another story for another day.

Peter